We tend to trust our eyes above all else, yet our visual system is far from a perfect recorder of reality. What we “see” is not a direct snapshot of the world but a constructed interpretation created by the brain from raw sensory data. Our eyes capture light and shapes, but it’s the brain that assembles, fills in blanks, and tries to make sense of what’s there. Because of this interpretive process, even tiny changes in angle, lighting, or timing can transform ordinary objects into something that appears strange, impossible, or unreal. A shadow at just the right moment can look like a stranger; a light bulb can be misread as a moon; a child’s posture can briefly resemble an animal form. These momentary misreadings occur because the brain constantly predicts and guesses what it expects to see, often filling gaps with plausible interpretations based on past experience rather than objective reality. This predictive process, while generally efficient, also creates fertile ground for illusions and misperceptions.

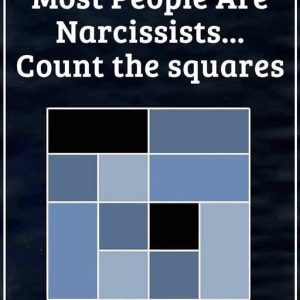

A key reason these visual mistakes are so captivating is that they reveal the fragile line between perception and reality. Our brains prioritize speed and efficiency in interpreting the world, using shortcuts and assumptions to keep up with the massive amount of visual data entering our eyes each second. This means that when information is ambiguous or incomplete, the brain fills in the blanks with what it expects to be there, not necessarily what is there. This phenomenon underlies many well-known illusions, like ambiguous figures and scenes that seem to shift shape depending on perspective. The concept is similar to how the brain interprets everyday images: it uses memory, context, and prior knowledge to produce a coherent picture—sometimes at the expense of accuracy.

The scientific term pareidolia describes one common way this happens: the tendency to see meaningful patterns in vague or random visual input. People might perceive faces in clouds, shapes in shadows, or familiar objects in chaotic backgrounds, even when no such forms exist. Pareidolia illustrates how the visual system pushes toward recognizable meaning, often creating it where none objectively exists. This reflects a deeper truth about perception: the brain constantly organizes visual stimuli into familiar categories to make sense of the world quickly and efficiently, even when the input is ambiguous.

Optical illusions take advantage of these built-in cognitive shortcuts and assumptions. They deliberately present visual information in ways that confuse the brain’s normal interpretive mechanisms. For example, illusions like the classic Necker cube appear to switch orientation simply because the brain tries to reconcile ambiguous depth cues into one consistent 3D interpretation. Other illusions exploit how the brain interprets contrast, shadow, and context to judge size, colour, or brightness incorrectly. These effects demonstrate a broader truth: perception is not a passive window onto objective reality but an active construction shaped by both sensory input and internal neural processes.

Neuroscience research shows that these perceptual errors are not accidents but built into how vision works. The brain processes visual input at multiple layers, constantly comparing what the eyes see against expectations informed by memory and prior experience. When illusions occur, it reveals how much the brain relies on internal models to interpret what should otherwise be ambiguous data. In some cases, examples like “The Dress” phenomenon—where people literally saw different colours in the same photograph—underscore that even basic qualities like colour depend on assumptions about lighting and context made by the brain. These assumptions help the visual system compensate for variable real-world conditions but can also lead to dramatically different interpretations of the same image.

Ultimately, the captivating nature of these photos and illusions lies in what they reveal about how we perceive the world. They remind us that our brains are not passive observers but active constructors of visual reality, constantly guessing and filling in missing information at lightning speed. This process is essential for navigating a complex environment but also makes perception surprisingly malleable. As a result, even a subtle shift in perspective, lighting, or angle can turn something familiar into something uncanny—prompting a momentary sense of confusion, surprise, or wonder. These experiences, while fleeting, highlight a deeper truth about human perception: what we see is only a model created by the brain, not the world itself, and sometimes that model gets it completely wrong—even as it strives to make sense of chaos.