At first glance, many optical illusions and ambiguous images trigger a startling reaction in the viewer because the brain’s instinctive interpretation doesn’t match visual reality. This phenomenon isn’t about the picture itself being strange; it’s about how our perceptual systems work. The human brain does not simply record visual input like a camera. Instead, it actively constructs a version of reality by filling in missing information, relying on experience, context, and neural shortcuts to make sense of what the eyes detect. When an image lacks clear cues about depth, lighting, or form, the perceptual system can produce “errors” that feel shocking or inexplicable until the brain settles on a different interpretation. This basic mechanism underlies why viral illusions make viewers pause, gasp, and then stare again — realizing their initial perception was incomplete or misleading.

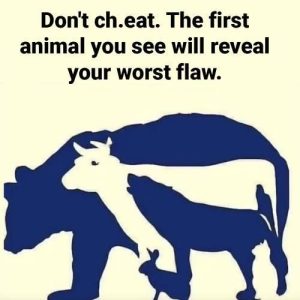

Psychologists and neuroscientists describe this kind of phenomenon as perceptual confusion, where the brain’s natural tendency to interpret incomplete patterns leads to multiple possible readings of the same visual input. In many well‑studied illusions, such as the Necker cube or Rubin’s Vase, the brain alternates between interpretations because the image provides ambiguous cues with no single definitive solution. These ambiguous figures demonstrate a key fact about perception: the brain prioritizes a rapid, useful interpretation over a slow, perfectly accurate one. Often, this means the brain uses experience‑based expectations — learned from past interactions with the three‑dimensional world — to resolve conflicting or limited visual information. While this strategy usually serves us well in everyday circumstances, in the context of carefully constructed illusions, it leads to surprising and sometimes disturbing misinterpretations.

Different people often see different things in the same ambiguous image because their brains make different assumptions about context, lighting, and depth cues. For example, the famous 2015 viral photo known as “The Dress” drew millions of views precisely because people disagreed on its colors — some saw it as blue and black, others as white and gold — and both interpretations were grounded in how each viewer’s brain assumed different lighting conditions. Variations in prior visual experience, such as habitual exposure to artificial versus natural light, influenced which version each person perceived first. This demonstrates that perception is not only about what’s in the image but also about what the brain brings to it based on previous experience.

The emotional responses triggered by such illusions — fear, curiosity, wonder, even disgust — arise because the perceptual system operates before conscious thought. When we encounter a visual pattern that doesn’t immediately resolve into a familiar object or form, our nervous system engages in rapid predictions and fills in gaps, often generating a strong instinctive reaction. These reactions are rooted in evolved survival mechanisms: in ambiguous visual conditions, quick judgments about motion or form could have once meant the difference between detecting a predator and ignoring a threat. While most modern visual environments don’t require such split‑second decisions, the brain continues to use these ancient perceptual shortcuts, creating fascinating misreadings when confronted with crafted illusions.

Optical illusions go viral not just because they trick the eye, but because they reveal the hidden processes behind perception that most people never consciously notice. They demonstrate that the brain’s first response is driven by fast, subconscious neural processing, while slower logical analysis comes later. This sequence — instinct first, reasoning second — explains why people often see something shocking or unsettling before understanding what they’re really looking at. Many illusions also depend on context: subtle surrounding elements can influence how the central figure is interpreted, leading to conflicting perceptions across observers. For instance, illusions that appear to show movement in static images rely on how motion‑sensitive neurons respond to repetitive visual patterns, creating the impression of motion where none exists.

So before scrolling past a viral illusion, it helps to remember that what you’re seeing is not just a quirky picture — it’s a window into the neural machinery of perception. By asking yourself not only what you see but also why your brain made that interpretation, you engage with how the mind integrates sensory input, prior expectations, and contextual cues to construct a coherent — even if imperfect — model of reality. Optical illusions remind us that seeing is not purely passive. It is an active, predictive process shaped by evolution, experience, and neural architecture. In doing so, they reveal a fundamental truth about human cognition: the mind does not merely receive images, it interprets them, predicts what should be there, and sometimes fills in blanks that aren’t actually present. The result is a dynamic interplay between perception and expectation, one that continues to captivate scientists and laypeople alike as they explore the fascinating boundary between perception and reality.