It seems counterintuitive that performing at the Super Bowl halftime show—one of the most watched live broadcasts on Earth—comes with no traditional paycheck. Yet this has long been the NFL’s rule. Regardless of stature, artists who headline the halftime show are not paid a performance fee. Instead, the event operates less like a concert booking and more like a global marketing exchange. The NFL frames the halftime show as a mutually beneficial cultural moment: the league provides unparalleled exposure, while the artist contributes a performance that elevates the spectacle without turning it into a paid endorsement.

Although artists don’t receive a salary, they are not expected to fund the show themselves. The NFL covers all essential production and travel costs, including staging, lighting, choreography, costumes, rehearsals, and technical crews. Since Apple Music became the halftime show’s title sponsor, those expenses have been supported through a large annual sponsorship deal with the league. From this partnership, performers are typically given a substantial production budget—often reported to be in the tens of millions—allowing them to create a visually ambitious, career-defining performance without personal financial risk. What they don’t receive is a check for appearing.

For artists, the real compensation is exposure—one of the rare cases where the word genuinely lives up to its value. The Super Bowl regularly draws well over 100 million viewers, offering an audience that surpasses even the biggest world tours. Historically, halftime performers see immediate spikes in streaming, downloads, and searches, often accompanied by renewed interest in tours, catalogs, and cultural relevance. The performance functions as a global relaunch, introducing artists to new demographics while reactivating longtime fans.

The benefits extend beyond music. Social media growth, brand value, and long-term influence often surge in the aftermath of a halftime appearance. To put that exposure in perspective, brands routinely spend millions of dollars for a single 30-second Super Bowl commercial, fully aware that the payoff lies in long-term recognition rather than immediate sales. A halftime performer, by contrast, receives more than ten uninterrupted minutes of global attention entirely focused on their identity, music, and message—something money alone can’t easily buy.

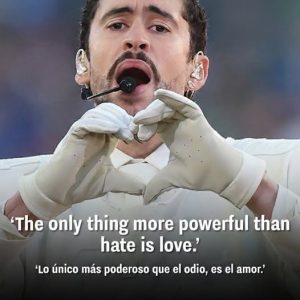

For artists like Bad Bunny, the halftime show also carries cultural and political weight. Known for using his platform to advocate for Puerto Rico, immigrant communities, and social justice, his appearance represented more than entertainment. Performing in Spanish on one of the largest American stages, he reframed the show as a celebration of identity and visibility. In that context, the absence of a paycheck mattered far less than the ability to speak to millions on his own terms.

Ultimately, the economics of the Super Bowl halftime show reflect a modern truth: attention is the most valuable currency. The NFL preserves a tradition that treats performers as cultural figures rather than hired acts, and artists continue to accept because the ripple effects—career momentum, influence, and legacy—far exceed the value of a single night’s fee. In a crowded media landscape, the halftime show remains one of the few stages powerful enough that performing for free still makes sense.